The Old Slovenes settled in the Valley between the end of the 6th and the beginning of the 8th century AD and became its first attested and documented inhabitants. It is believed that they might have come from the Mea Valley. However, another thesis, backed up by cultural elements, has also been put forward, suggesting a connection between these peoples and those of the Upper Natisone, the Middle Soča, and the Cornappo Valley. On this premise it is possible to speculate about a route that went across the Kobarid pass and up the Natisone Valley. The routes then branched off on the slopes of the Zuffine mountains, the Carnizza di Monteprato Pass, and the Gran Monte. The paths that give evidence of this connection were traced at higher altitudes, avoiding the valley floor, and connected the villages of Monteaperta, Montemaggiore, Lusevera, Taipana, Subit, Porzûs, and Canebola.

Room 1. General information

Interesting evidence of these contacts is represented by the centrality of the Holy Trinity cult (Sveta Trojica) in Monteaperta, a sacred and notoriously old place (11th-12th century), the destination of many pilgrimages that attracted (and still attracts) all the Slovene populations of the conterminous areas. Contacts with the Friulian world, on the other hand, were scarce.

There is an almost complete lack of information on the Torre Valley territory: the authorities that followed one another and were in charge of the area didn’t take good care of the life conditions of the community that had settled there.

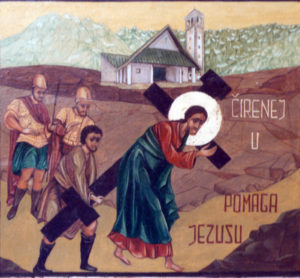

Religion

Since their conversion to Christianity in the 9th century, which had been the work of missionaries under the Patriarchate of Aquileia, the Slovenes in the Torre Valley had only laid claim to their right to have a priest of “sclabonic” language. But it seems that the requirement of having a Slovene-speaking vicar was largely disregarded. It is for this reason that the populations in the mountains became restless. In 1606 Tarcento’s priest was put on trial. The sentence decreed the right of the mountain villagers to elect a Slovene-speaking chaplain every three years. In 1607 the Patriarch of the Aquileian diocese’s great reform, Francesco Barbaro, founded a specific Slavic vicariate, the “vicariatus sclaborum”, which merged the ten Slavic villages of Coia, Sammardenchia, Stella, Zomeais, Ciseriis, Sedilis, Villanova, Lusevera, Pradielis, and Cesariis. The Slovene-speaking vicar, however, stayed at home in Tarcento most of the time, and rarely made an appearance in the chapels of the other Slavic villages. The vicariatus lasted over one year, until 1730, when the small villages of Lusevera, Pradielis, and Cesariis asked to separate from the stipulated union in order to self-manage their religious life.

At the museum’s entrance you can see some objects connected to religious life. Among these, it is important to notice the iron host mould in the shape of pincers, with sacred images engraved on one side that the priest could imprint on the hosts. On the small table there is a mould for the hosts that were to be offered to the devotees.

On the left, a box with a crank is displayed on the floor: it is a tool which was used to make noise that would substitute the church bells on Good Friday. The ratchet (or noisemaker) served the same purpose, as it was an instrument consisting in a dented wheel, which, when moved in circles by a crank, plucked a wooden plate with its teeth, producing a characteristic noise that was similar to a frog’s croak.

A religious practice for good luck that is still in use in Lusevera is the koleda, the collecting of alms: on the first day of the year the children go from door to door and recite a rhyme in exchange for gifts: “Koledo novo lieto, Buoh nam dejte no doró lieto!” “New year’s koleda, God give us a good year!”

Altri oggetti

The other objects that are exhibited in the first room were used by the families for housekeeping. On the wall there are some wooden arches with a hook at each end that were used to hang two buckets full of water gathered at the sources.

Under them there are some barrels that were also used to carry water.

On the shelf on the side there are two kinds of lanterns which could light up the space by combusting oil or petroleum. Before the lanterns, the lighting was provided by the “luč”, a stick of about 10-12 cm in length made of dried and aged larch roots, which were later reduced to twigs measuring about 4-5 mm in diameter. These twigs were inserted into the wall between one stone and another, and lit at one end with an ember taken from the fireplace.

Under this, next to the sewing machine, you can notice some wooden objects in the shape of eggs that were used to mend socks.

The room also contains two nuptial desks, both very simple. Weddings didn’t require big celebrations: the bride and groom dressed poorly and had clogs on their feet. The bride, going out of the house, followed the groom without carrying anything. After the church ceremony, the newlyweds went home for the wedding lunch. The wealthy could enjoy the “ocikana”, polenta dumplings with cheese and melted butter, the poor some polenta and frico. Then, on the same day, they went to work in the fields and woods.

If the bride wasn’t from the same village as the groom, the village’s youth blocked the way back from the reception with a pole, a wooden log, and demanded that the groom pay them a sum of money. After the payment, the pole was lifted and the celebrations could continue. At dusk, the bride went alone back to her father’s house to receive the dowry.

Other interesting objects in the room are a cutting board with an iron blade in the middle and an iron baskets for picking up vegetables.You can also notice two wooden cheese drainers and a mortar for chestnuts containing a large stomp with a long handle and a pestel that is reinforced with iron foils.

On the table there are some salami-making tools made of wood or obtained from an emptied horn. The insides were covered with animal intestines and then filled with meat.

It is worth noticing that the biggest chair has the owner’s initials engraved in it. This was considered a sign of recognition when everyone took their chair to a bereft family’s house to say the rosary.

On the chair there are two bellows that were used to fan the fire.

On the andiron two barley toasters are hung, long “pliers” with a sphere on top that could be divided into two halves. The spherical part was filled with barley and put on the fire for toasting.

The people used a lot of tobacco: they smelled it (even the women), chewed it, or smoked it using pipes with a long mouthpiece.

Multimedia

The multimedia installation presents some interesting videos regarding:

- the cross kissing ritual in the Holy Trinity church,

- the Madonna of Health procession in Lusevera,

- the works of the San Floriano church in Villanova delle Grotte,

- the song “Tam dol teče voda rajna”, recorded in Platischis in the 1960s by researcher Pavle Merkù. It was sung by Slovene devotees when, every seven years, they went on pilgrimage to Aachen. Such pilgrimages ended after the Protestant Reformation in the first decade of the 16th century.

- The last video recounts the story of the apparition of the Madonna in Porzus on 8th September 1855, told in the Slovene dialect of Subit with Italian subtitles. The Madonna appeared to little Teresa Dush, 10 years old at the time, while she was picking grass to feed the cows on a feast day. The Holy Mary took the sickle out of her hand, smiled at her, and said sweetly, in the Slovene dialect of the Torre Valley: “You mustn’t work on feast days!” The Madonna bent down, cut a handful of grass, and gave it to the child, saying: “Take this, it will be enough.” Then she gave her the task of reminding everyone to sanctify the Lord’s name, not to swear, and to observe fasts and wakes.